You are here

Science Resources: Water and the Law

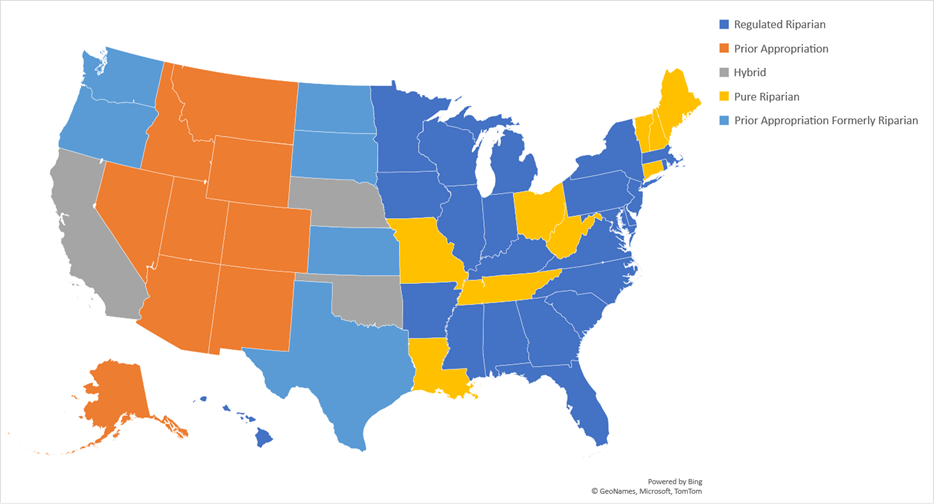

SIDEBAR: By the Books – An Overview of Surface Water Use Rights in the United States

In the United States, private rights to use water are governed by state law. Depending on the state, one of three approaches is followed:

1. Riparian rights tie the right to use water to ownership of land adjacent to a river, stream, lake, or pond from which water may be drawn. This approach is typically taken by states with a more humid climate in which rivers flow year-round and is more commonly found in the eastern United States. Here are a few important characteristics:

- Riparian rights require that any use of the water be “reasonable.” Reasonableness is usually determined by comparing the proposed use against uses by other riparian landowners and considering whether it interferes with the rights of downstream riparian landowners.

- Persons who do not own land adjacent to rivers, streams, lakes, or ponds do not have the right to use water found therein. In some jurisdictions, they may purchase the right to use water from riparian landowners. Sometimes, use of the purchased right is conditioned on the proof of no actual harm to downstream users.

- Most states have regulated riparian rights, tied to permits issued by a central governing body. These permits govern who may use the water and how much and when they can use it. Issuing permits helps states to better forecast future uses, as well as to ensure existing uses are compatible.

- Because riparian rights are tied to the adjoining land, nonuse of a right does not extinguish it. However, state-issued regulated riparian right permits do have fixed time limitations (typically several years), after which the permit must be renewed.

2. Prior appropriation rights can be summed up by the adage “first in time, first in right.” This approach is typically used by states in the western United States in arid areas without year-round rivers or streams. Here are a few important characteristics:

- In contrast to riparian rights, there is no equitable reduction in rights for all users during times of shortage. Instead, the senior user may enforce “call of the river” to receive their full share of the appropriation before junior users receive theirs, even if the junior user is upstream. The only time when this is not the case is when the senior user’s share of water would be lost to evaporation in transit (a “futile call”).

- To have a valid appropriation, the user must show an intent to make beneficial use of the water. Historically, this intent was validated by the physical diversion of the water from the relevant water body. Now, an application for a permit can show the necessary intent.

- The user must then apply the water to a beneficial use to “perfect” the right. In doing so, the right is given seniority over all following use claims. Note that some states place the date of seniority at the permit application date, rather than the date when the use is perfected.

3. Hybrid rights combine aspects of the riparian and prior appropriation doctrines into a single permit system managed at the state level. Eleven states have various forms of hybrid rights:

-

Hybrid: California, Oregon, and Washington

-

Prior Appropriation (Formerly Riparian): Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Nebraska.

-

Prior Appropriation: South Dakota, North Dakota, Mississippi, and Hawaii