You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

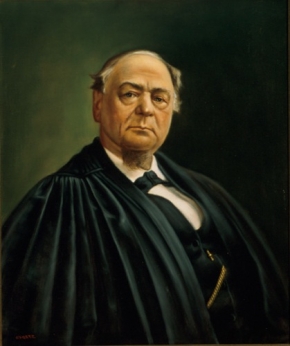

Associate Justice Noah Haynes Swayne, United States v. Rhodes (1866)

United States v. Rhodes, 27 F. Cas. 785 (C.C.D. Ky. 1866) (No. 16,151) [Sixth Circuit]

United States v. Rhodes produced the first federal court opinion interpreting the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which protected rights its drafters deemed essential to citizenship. The defendants, whites convicted under the act for burglarizing the home of an African American woman, sought to have their convictions overturned on the grounds that the act was unconstitutional. The U.S. district judge for Kentucky, Bland Ballard, wrote to Chief Justice Salmon Chase, asking him to send the circuit justice, Noah Swayne, to sit on the case with him. After consulting with U.S. Senator Lyman Trumball, who wrote the 1866 act, Swayne traveled to Kentucky.

Justice Swayne relied on the Thirteenth Amendment, ratified in 1865, in upholding the Civil Rights Act. Swayne noted that under the common law, all those born in the United States were citizens, with two exceptions: the children of ambassadors, and enslaved people. The Thirteenth Amendment, by ending slavery, had automatically operated to make citizens of the formerly enslaved, he held. The provision of the Civil Rights Act conferring such citizenship and the rights pertaining thereto was therefore only restating the law under the Thirteenth Amendment. “The present effect of the amendment,” Swayne wrote, “was to abolish slavery wherever it existed within the jurisdiction of the United States. In the future it throws its protection over every one, of every race, color, and condition within that jurisdiction, and guards them against the recurrence of the evil. The constitution, thus amended, consecrates the entire territory of the republic to freedom, as well as to free institutions.”

In sum, Swayne viewed the Thirteenth Amendment as taking away from the states the power to determine whether African Americans within their borders would be enslaved or free. To leave it at that, however, would have allowed the former slave states to pass oppressive legislation continuing slavery in all but name. “Blot out this act and deny the constitutional power to pass it, and the worst effects of slavery might speedily follow. It would be a virtual abrogation of the amendment,” he concluded. Other judges followed Swayne in upholding the act of 1866, and the act’s citizenship provision was incorporated into the Fourteenth Amendment, ratified in 1868. Nevertheless, the broad conception of national citizenship Swayne articulated in Rhodes was rejected by the Supreme Court in the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873).