You are here

Supreme Court Meeting Places

The Federal Judicial Center’s history page houses a rich gallery of federal courthouses. This collection presents several hundred images of buildings that have housed federal courts. The only entry for the Supreme Court of the United States is its current building: the iconic neoclassical temple of justice located across First Street Northeast from the U.S. Capitol in Washington, D.C. One could be forgiven for assuming that this building is the only home the Court has ever known. And, indeed, the Supreme Court building very deliberately conveys a sense of timelessness, echoing the temples of Mediterranean antiquity. Yet the building has been the Court’s home for less than ninety years, and the Court has met in several other buildings in three different cities. None of these was a bespoke federal courthouse. This spotlight details several of these sites and explains the reasons the Court has moved so many times and took nearly a century and a half to gain a home of its own.

Section 1 of the Judiciary Act of 1789 dictated that the Supreme Court hold two sessions each year “at the seat of government,” but Congress did not provide for the Court’s accommodations in New York City, which then served as the national capital. This may seem like a strange oversight today, when federal courts are generally housed in large, purpose-built federal buildings. In the nascent republic’s first several decades, however, the federal government had limited funds and a vanishingly small physical footprint. Federal courts around the nation typically conducted business in state courthouses or more makeshift accommodations like meeting halls or taverns. As the federal government grew over the course of the nineteenth century, courts frequently met in post offices or customs houses—two of the primary sites of federal governmental activity. However, they were rarely housed in buildings whose chief purpose was judicial until around the turn of the twentieth century.

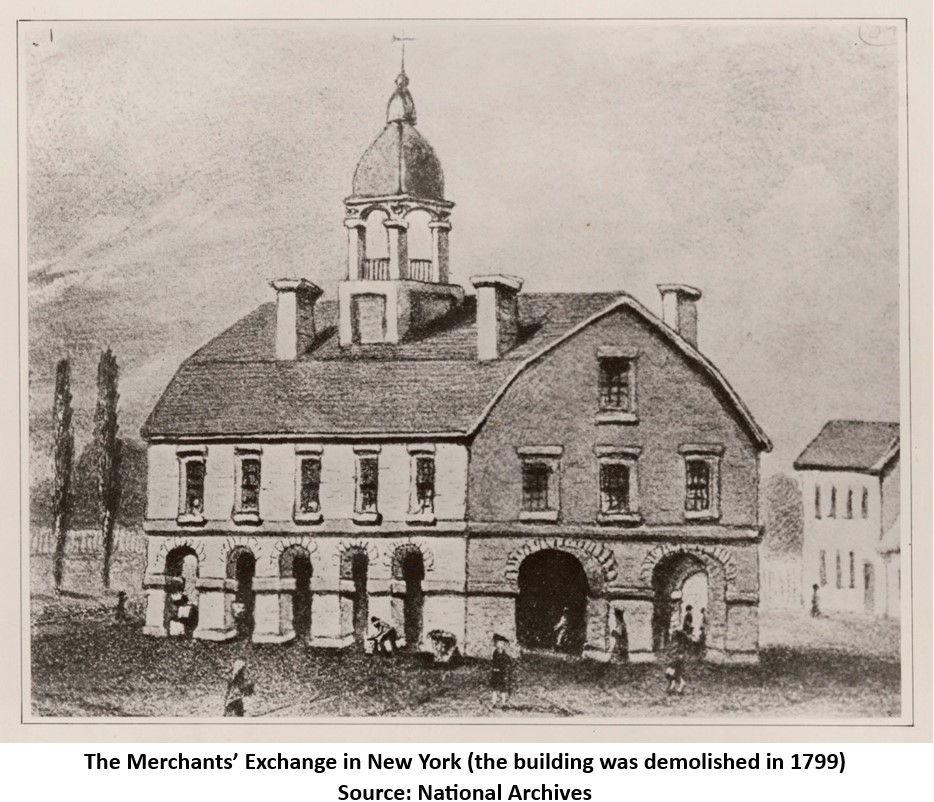

The Supreme Court initially followed this pattern. The Court met for two sessions in 1790 at the Merchants Exchange in New York. This building, which also housed the U.S. District Court for the District of New York, was originally constructed in 1675 as the Royal Exchange, but had been rebuilt in 1752 and renamed after the American Revolution (ca. 1775–1783). It had housed the state’s legislature from 1785 and continued to do so during the brief time the Supreme Court met on its second floor.

The two sessions the Supreme Court held in New York took place in February and August. As the Court did not yet have any cases to hear, both sessions were exceptionally brief by modern standards (the first lasted ten days, the second just two). The Court’s business was primarily focused on administrative tasks such as the appointment of staff and the admission of attorneys to the bar. The justices also issued orders pursuant to their inherent and statutory powers to “make and establish all necessary rules for the orderly conducting business,” though these orders were not compiled in a single document until 1828 and were not fully organized as a cohesive body of procedural rules until 1954. (See Rules: Pre-1934 Rulemaking.)

Congress soon cut short the Court’s stay in New York. In 1790, lawmakers passed the Residence Act. This law reflected a compromise between political blocs led by New Yorker Alexander Hamilton on one side and Thomas Jefferson and James Madison of Virginia on the other. The factions agreed to move the seat of government to a site near Virginia in return for the national government’s assumption of Revolutionary War debts owed by New York. The Act relocated the national capital to a ten-square-mile area spanning the Potomac River, the land for which was ceded to the nation by Virginia and Maryland. This grant reflected Article I, Section 8’s provision for a potential congressionally supervised capital district to be created “by Cession of particular States, and the Acceptance of Congress.” The same legislation designated Philadelphia as a temporary capital until the relocation to what would become the District of Columbia. This temporary relocation was necessary because the district was not yet sufficiently developed to serve as a capital city.

With the temporary movement of the seat of government, the Supreme Court had to relocate to Philadelphia to comply with the terms of the Judiciary Act. Along with many of the major apparatuses of the federal government, the Supreme Court met in the buildings that now comprise Independence Square in the Independence National Historical Park. The Court held its two-day February 1791 term in Independence Hall, which had played host to debates over both the Declaration of Independence in 1776 and the Constitution of the United States in 1787. From that point on, the Court conducted most of its business in the recently constructed City Hall (now widely known as Old City Hall). For most of the 1790s, the Court met on the ground floor of the building, while the city government occupied the upper floor (the Court also held a brief session in August 1800 in a nearby building). The refurbished chamber is sometimes available for public viewing.

Though it finally began deciding cases later in 1791, the Supreme Court that met in Philadelphia was still not the august institution it later became. Throughout its time there, the justices labored to define their roles and the place of the Court as an institution in the new constitutional order. It seems that at least some of the early justices felt that other state and federal offices offered more prestige and influence. Associate Justice John Rutledge left the Court in 1791 to serve on the South Carolina Court of Common Pleas, for instance. Due to this and several unrelated factors, the earliest cohort of justices generally had short tenures. Indeed, only two of President George Washington’s ten Supreme Court appointees were still on the bench by 1807.

When Chief Justice John Jay resigned his post in 1795 to become Governor of New York, President Washington gave a recess appointment to former Justice Rutledge. Rutledge was not confirmed by the Senate, however, mostly due to his controversial stance against a treaty with Britain. As a result, his tenure lasted only five months. Washington’s third pick for Chief Justice, Oliver Ellsworth, did gain Senate approval in 1796, but resigned in December 1800, just as the Court was set to move to the District of Columbia (while the Residence Act anticipated that the government would move by December 1, the court’s next session was not due to open until the following February). Ellsworth, who was abroad in his concurrent capacity as an envoy to France, likely resigned due to ill health rather than an unwillingness to move.

As a result of Ellsworth’s resignation, the Court’s move to the District of Columbia corresponded with the transformative chief justiceship of his successor, John Marshall. Many historians credit Marshall and, to a lesser extent, likeminded Justices like Bushrod Washington (appointed in 1798) and Joseph Story (appointed in 1811) with setting the Court on the path to becoming a powerful arbiter of major constitutional issues. That such an evolution was not inevitable is arguably demonstrated by the Court’s treatment during the move to Washington.

Although the Residence Act switched the seat of government to the District of Columbia effective 1800, it again made no provision for the Court’s accommodation there, despite requiring a suitable house for the President and a grand purpose-built meeting place for Congress. Shortly before the Court’s first session in Washington was due to begin, Congress finally passed a resolution allowing the Court to use a room in the lower floor of the partially completed U.S. Capitol. The Court was to remain in that building for the next 134 years.

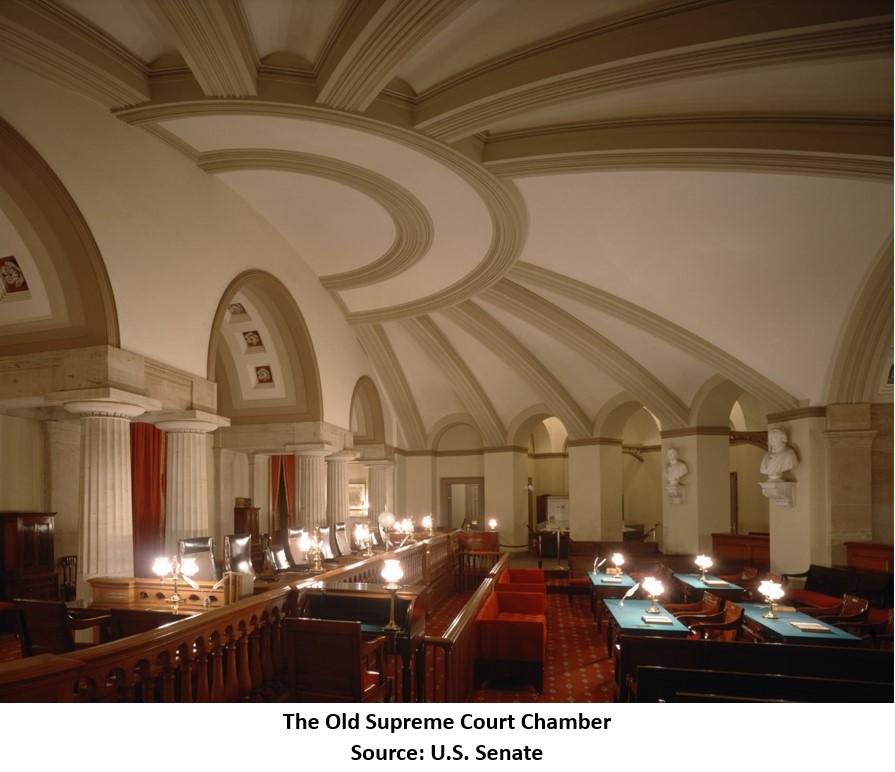

Though only recently constructed, parts of the Capitol proved structurally unsound and required extensive renovations. As part of these renovations, the Court’s accommodations were refurbished to serve as a more permanent courtroom, now known as the Old Supreme Court Chamber, starting from 1810. Designed by architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the room is noted for its semicircular vaulted ceiling, which was unusual in America at the time and considered a major architectural achievement.

Not long after taking residence in this space, however, the Court had to vacate the Capitol in August 1814 after British troops set fire to the building as part of their sack of Washington during the War of 1812. During the period of reconstruction that followed the fire, the Court met in a local tavern and later in a room in the North Wing of the Capitol. The Court was finally able to return to the restored chamber in February 1819.

After the Court left the Old Supreme Court Chamber in 1860, the space served as the Law Library of Congress. Subsequent to the Court leaving the Capitol for its own building in 1935, the room was used for several other functions including use by the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy in the 1950s. It was restored to its mid-nineteenth-century appearance in 1975 and is sometimes available for public view.

The chamber is notable for its busts of former Chief Justices. Though Roger Taney was the last person to preside over the Court in its new chamber, Congress did not initially authorize a bust for him to rest alongside those of the other chiefs. This refusal was motivated by Taney’s infamous opinion in Scott v. Sandford (1857), a decision most historians agree heightened the sectional tensions over slavery that eventually culminated in the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865). His bust was eventually placed alongside those of the first four chief justices at the rear wall of the room. However, Taney’s bust was moved to a cloakroom near the entrance to the during the 1975 restoration to reflect the space’s appearance in the 1840s. In December 2022, however, Congress passed a law ordering the removal of the bust and its eventual replacement by one of Justice Thurgood Marshall (Taney’s fellow Marylander and a champion of civil rights as both an advocate and judge).

After extensive refurbishments and expansions of the Capitol Building in 1860, the Court moved up to the first floor of the building, occupying the larger, two-story chamber vacated by the U.S. Senate the previous year. This space played host to hearings in many of the Court’s most important decisions over the course of the seventy-five years the Court was housed there. Like the Old Supreme Court Chamber, the Court’s second permanent home in the Capitol Building was restored in celebration of the nation’s bicentenary (though the restoration returned the space to its condition as a Senate chamber, rather than as a courtroom).

In some sense, the push for the Supreme Court to gain its own building reflected the rationalizing ethos of the first decades of the twentieth century. This period is often associated with the growth of the administrative state and the reorganization of government in the interest of a more harmonious and rational organization. One of the foremost champions of this approach was William Howard Taft, the only person to serve as both President and Chief Justice. In the latter capacity, Taft pressed for a vision of the federal courts as an autonomous branch of government that could and should be responsible for administering its own affairs without the need to rely on the administrative apparatuses of the executive branch or, in the case of his own court, the physical plant of Congress. In this sense, the construction of the building complements two other major developments during Taft’s tenure as Chief Justice: the 1922 founding of the Conference of Senior Circuit Judges (now the Judicial Conference of the United States), the governing body of the judicial branch; and the Judges’ Bill of 1925, which gave the Supreme Court substantial control over its appellate docket.

In Chief Justice Taft’s view, there were also compelling practical reasons for the Court to move into its own building. A raft of courthouse construction projects in the early twentieth century had led to the somewhat anomalous situation of many inferior federal courts having impressive, purpose-built facilities while the highest court in the land had to make do with limited space in a shared building. Taft wrote repeatedly to lawmakers complaining that there were little-to-no facilities for lawyers to prepare for arguments and such restricted office space that the justices were forced to work from home.

Chief Justice Taft’s lobbying efforts were repaid in 1928, when Congress authorized the creation of the Supreme Court Building Commission to “procure . . . preliminary plans and estimates of costs for the construction, and the furnishing and equipping, of a suitable building . . . for the accommodation and exclusive use of the Supreme Court of the United States.” The Commission consisted of Taft, who served as its chair, an associate justice (Willis Van Devanter eventually filled this role), members of relevant congressional committees, and the Architect of the Capitol. The statute creating the Commission stipulated that the building would be located in recently acquired land across the road from the Capitol and adjacent to the Library of Congress. It also required that the exterior of the building “be of such type of architecture and material . . . as to harmonize with the present buildings of the Capitol group.”

Cass Gilbert, the architect Taft selected to draw up plans, aimed to meet this brief, as well as Taft’s insistence that the building reflect the Court’s dignity and authority by designing the building in the neoclassical revival style with a façade dominated by large marble steps and a grand portico supported by Corinthian columns. This aesthetic and the prevalent use of marble arguably belied what was a modern design, with the marble encasing a steel frame.

Congress approved the plans drawn up by Gilbert and the Commission in 1929, appropriating $9,740,000 for the construction and the demolition of existing buildings on the site. Taft did not live to see the building’s completion. He resigned due to ill health on February 2, 1930, and died on March 8. Construction began in earnest in 1932 and was completed in 1935, with the building coming in under its initial budget.

Winston Bowman, Associate Historian

For more information, contact history@fjc.gov

Related FJC Resources:

Maps of Federal Court Authorized Meeting Places

Further Reading:

Resnik, Judith. “Building the Federal Judiciary (Literally and Legally): the Monuments of Chief Justices Taft, Warren, and Rehnquist,” Indiana Law Journal, vol. 87 (2012): 823.

“Residences of the Court: Past and Present; Part II: The Capitol Years,” Supreme Court Historical Society Quarterly (Winter 1981): 2–4.

Supreme Court of the United States, Meeting Sites of the Court.

Architect of the Capitol, Supreme Court Building.

This Federal Judicial Center publication was undertaken in furtherance of the Center’s statutory mission to “conduct, coordinate, and encourage programs relating to the history of the judicial branch of the United States government.” While the Center regards the content as responsible and valuable, these materials do not reflect policy or recommendations of the Board of the Federal Judicial Center.