You are here

The Midnight Judges

After the acrimonious election of 1800, Congress passed controversial legislation increasing the size and transforming the structure of the federal judiciary. In the final weeks of his presidency, John Adams (who had lost the election to his great rival Thomas Jefferson), nominated, and the U.S. Senate quickly confirmed, several new federal judges. Secretary of State and Chief Justice John Marshall raced against time to deliver the judges’ commissions, failing to distribute some on Adams’ final day in office because there were too many documents to carry. The successfully appointed judges have gone down in history as the “midnight judges”—a phrase that both evokes last-minute maneuvering and casts doubt on the judges’ legitimacy. Adams’s political adversaries claimed he had appointed these men to pack the federal judiciary with partisan cronies. This spotlight explores the context for the judges’ appointments, so that readers may better evaluate these claims.

The election of 1800 was a watershed moment in American history. For the first time, control of the federal government passed from one political party to another. Many of the Constitution’s framers hoped that it would serve as a bulwark against the emergence of permanent political factions. Over the course of the 1790s, however, the lines between two broad political coalitions became increasingly well defined. Politicians in these two groups staked out differing positions on several major issues, including the appropriate size and role of the federal judiciary.

In the 1800 election, Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans (also known as Jeffersonians) won a decisive majority over the reigning Federalists in Congress. Jefferson’s own victory in the presidential election was complicated by a tie in the Electoral College with his de facto running mate Aaron Burr. It took thirty-six ballots for the House of Representatives, which still contained several “lame duck” Federalists, to select Jefferson. The new Congress and president were due to take over on March 4, 1801.

While the peaceful exchange of power from one party to another has become a much-praised commonplace in American politics, many Federalists deemed the looming transfer as something approaching a coup. In the Federalists’ view, Democratic-Republican critiques of existing policies were tantamount to disloyalty and sedition rather than the statement of reasonable differences. In their final weeks in power, Federalists attempted to find ways to influence the government to take a course closer to their vision while they were out of power.

The Judiciary Act of 1801, passed on February 13, was arguably the Federalists’ most important attempt to accomplish this goal. This law reordered the federal judiciary in several important ways. Among other innovations, the Act dispensed with the need for Supreme Court justices to “ride circuit,” a process by which justices endured onerous travel to preside over trial courts around the country. Instead, the law created regional circuit courts to be staffed by a new group of circuit judges. Passed late in President Adams’s term, the Act gave him the opportunity to appoint several judges just as he was leaving office.

Jeffersonians cried foul. They argued that the Judiciary Act was a cynical exercise designed to place Federalist sympathizers on the bench with a view to blunting the incoming government’s policies. Though Jefferson would undoubtedly have his own judicial vacancies to fill in time, the large number of new appointments under the 1801 Act might dilute the influence of Jefferson’s appointees. Many Jeffersonians vowed to remove the “midnight judges” from office by repealing the Judiciary Act.

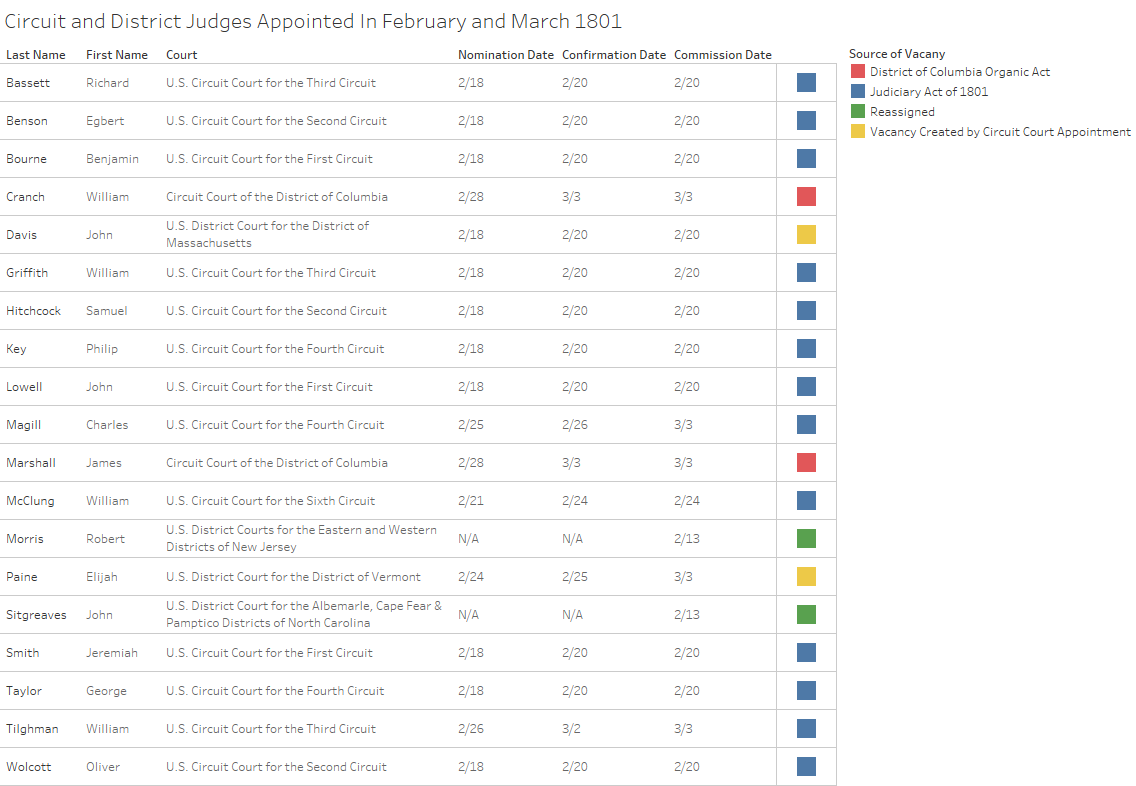

As an indication that the judges were nominated and confirmed quickly and late in Adams’ term, the “midnight judges” label was undoubtedly merited. The chart below shows the nomination, confirmation, and commission dates of the Article III judges appointed in February and March of 1801. The nominations process tended to be quicker in the early nineteenth century than it is today; nominees did not undergo the same rigorous background checks and Senate hearings that their modern counterparts must endure. Even so, it is remarkable that so many judges were confirmed so quickly at the end of Adams’s term.

All but four of the nineteen successful judicial nominees from the end of Adams’s term were appointed to courts created by legislation promulgated in his last month in office. The term “midnight judges” is usually applied to the circuit judges appointed to judgeships instituted by the Judiciary Act of 1801. However, William Cranch and James Marshall (the Chief Justice’s younger brother) were also appointed to the new Circuit Court for the District of Columbia. This court was created by legislation passed on February 27, 1801, which established the government and legal system of the nation’s new capital. Judges John Davis and Elijah Paine were appointed to District Court positions rendered vacant by the appointment of district judges John Lowell and Samuel Hitchcock to new circuit courts. Two existing district judges were also reassigned due to the creation of new districts in their states under the Judiciary Act.

If the swiftness of all these appointments is clear, it is harder to evaluate the more pejorative implication of the “midnight judges” label—that Congress and the President had packed the judiciary with political clients. The Judiciary Act of 1801 reflected many ideas Federalists had championed throughout the 1790s. Although the Constitution stipulated the creation of the Supreme Court, it left decisions over whether to create “inferior” federal courts to Congress. This arrangement reflected disagreements at the Constitutional Convention as to the size and composition of the new judiciary, and those issues continued to divide early Congresses. The initial blueprint for the judiciary reflected a series of political compromises between emerging Federalists, who advocated for a robust federal judiciary, and proto-Jeffersonians who wanted to limit the size of the judiciary and entrust most cases to state courts. The 1801 Act achieved many of the Federalists’ long-term goals by giving federal courts jurisdiction over cases arising under federal law (also known as federal question jurisdiction), rearranging circuits, and staffing the circuit courts with their own judges. The Act gave federal judges more power, but that result was consistent with longstanding Federalist ideology as much as with cynical opportunism.

There is little evidence for the notion that the judges themselves were partisan hacks. In addition to the successful nominations listed above, six of Adams’ nominees to new circuit court seats declined their commissions. Many of them rejected their appointments out of practical concerns or because they worried that the Democratic-Republicans would repeal the Judiciary Act.

However, their refusals at the very least suggest a lack of close coordination between the Adams administration and several of the nominees. Jefferson also elevated Judge Cranch (one of Adams’ last appointees who is nonetheless usually distinguished from the midnight judges) to chief judge of his court in 1806. Jefferson was unlikely to promote a died-in-the-wool Federalist partisan. And indeed, Cranch went on to become one of the longest-serving and most venerated judges of the nineteenth century.

Many of the other judges Adams appointed at the end of his tenure had impressive resumes. Though their denigrators might point out that many of these appointees had distinguished themselves in Federalist political roles, several also had substantial prior judicial service. Richard Bassett, for example, had served as both a U.S. senator and governor of Delaware, but he had also been chief justice of a Delaware court for six years. Egbert Benson had been a Federalist congressman, but he was also a framer of the Constitution who had served as a justice on New York’s Supreme Court of Judicature for several years. Three of the appointees—Lowell, Hitchcock, and Benjamin Bourne—were sitting district judges. Oliver Wolcott, who had served as Adams’s secretary of the treasury, arguably had the least legal experience of any of the midnight judges. Treasury experience, however, proved a common path to the federal bench after Wolcott’s time. Indeed, three Chief Justices of the United States were appointed to their positions directly after serving in the same role as Wolcott.

These factors were not sufficient to persuade Democratic-Republicans of the judges’ bona fides. Approximately a year after coming to power, the Jeffersonians passed legislation repealing the Judiciary Act of 1801. Their replacement Judiciary Act abandoned federal question jurisdiction (thus returning most cases predicated on the Constitution and federal statutes to state courts), restored circuit riding duties for Supreme Court justices, and replaced the circuit courts established by the 1801 Act. Together, these two laws had the effect of removing the midnight judges from office by abolishing their courts. Judges appointed to the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia, however, retained their commissions.

The repeal of the 1801 Act and the subsequent promulgation of the new Judiciary Act prompted considerable constitutional debate. Many Federalists argued that the repeal of the 1801 Act was unconstitutional because it had the effect of removing Article III judges from offices they held “during good Behaviour.” Some (including Chief Justice Marshall) also believed that the Judiciary Act of 1802 improperly required Supreme Court justices to hold circuit courts without having been appointed to serve on those courts. Nevertheless, in Stuart v. Laird (1803) the Court held that there were “no words in the Constitution to prohibit or restrain” Congress’s power to reform the courts as it had done. (Marshall did not vote in the case because he was involved in earlier proceedings).

Stuart reflected a gradual acceptance of the Jeffersonians’ power to shape the judiciary. As the structural arrangements set by the Judiciary Act of 1802 became entrenched over time, the short-lived 1801 Act and the judges appointed under it slowly assumed an air of evanescence and illegitimacy. Nevertheless, many of the repealed Act’s innovations eventually became law in other forms. In 1869, for example, Congress again created dedicated circuit-court judgeships. This limited the mandatory practice of circuit riding, though that practice was only formally eliminated later. In 1875, Congress restored federal question jurisdiction, which has formed an important part of the federal judiciary’s role ever since. And, since removing three judges from the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia in 1863, Congress has reassigned judges from defunct courts rather than removing them from office. These later developments counsel caution in dismissing out-of-hand either the 1801 Judiciary Act or, by implication, the judges appointed under it.

Winston Bowman, Associate Historian

For more information, contact history@fjc.gov

Related FJC Resources:

Read the full text and analysis of the Judiciary Acts of 1801 and 1802 and learn about the judges mentioned here as well as all Article III judges in the Biographical Directory of Article III Judges, 1789–present.

Read more about the Judiciary Act of 1801 and its repeal with primary sources in Ragsdale, Bruce A. Debates on the Federal Judiciary: A Documentary History, vol. I: 1787–1875. Washington: D.C., 2013.

Further Reading:

Ackerman, Bruce. The Failure of the Founding Fathers: Jefferson, Marshall, and the Rise of Presidential Democracy. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Glickstein, Jed. “After Midnight: The Circuit Judges and the Repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801.” Yale Journal of Law and the Humanities 24 (Summer 2012): 543.

LaCroix, Alison L. The Ideological Origins of American Federalism. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2010.

Lukens, Robert J. “Jared Ingersoll’s Rejection of Appointment as One of the Midnight Judges of 1801: Foolhardy or Farsighted.” Temple University Law Review 70 (1997): 189.

Turner, Kathryn. “The Midnight Judges.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 109 (1961): 494.

This Federal Judicial Center publication was undertaken in furtherance of the Center’s statutory mission to “conduct, coordinate, and encourage programs relating to the history of the judicial branch of the United States government.” While the Center regards the content as responsible and valuable, these materials do not reflect policy or recommendations of the Board of the Federal Judicial Center.