You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

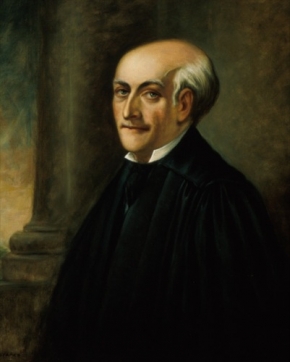

Associate Justice Henry Brockholst Livingston, United States v. Hoxie (1807)

United States v. Hoxie, 26 F. Cas. 397 (C.C.D. Vt. 1807) (No. 15,407) [Second Circuit]

In Hoxie, Justice Livingston provided one of the first judicial interpretations of the Constitution’s definition of treason. His charge to the jury established the principle that an act committed for private rather than public purposes did not constitute “levying war” against the United States. The case was also reflective of Livingston’s tendency to construe the criminal law narrowly, particularly in cases involving the death penalty.

The defendant was a member of a group that stole a barge from customs officials who had seized it before it could be smuggled into Canada. During the theft, the men fired shots at troops guarding the barge but did not injure anyone. Charging the jury after trial, Livingston emphasized that treason, being the most serious crime, was defined only by the Constitution, rather than being left to Congress like other crimes. To prove treason, he explained, the government had to establish at least one of two elements: that the defendant had levied war against the United States, or had adhered to the nation’s enemies, giving them aid and comfort. Because the United States had no declared enemy at the time, Livingston told the jurors they needed to consider only the first element.

Livingston left the jury with no doubt that he did not believe the defendant’s actions constituted treason. The crime, he said, was “nothing more than the forcible rescuing of a raft from the custody of a military guard.” “It is impossible,” he continued, “to suppress the astonishment which is excited at the attempt which has been made to convince a court and jury of this high criminal jurisdiction, that, between this and levying of war, there is no difference.” The act had clearly been committed solely for the purpose of private gain, Livingston asserted, and not with the aim of challenging the authority of the government as had been the case with the Whiskey Rebellion and the Fries tax revolt. Livingston acknowledged that the defendant had committed a crime but believed that the government could have charged him under criminal statutes carrying less severe penalties. After hearing Livingston’s charge, the jury quickly acquitted Hoxie.