You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

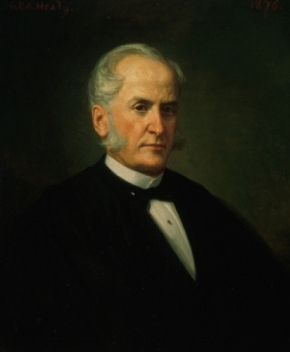

Associate Justice Ward Hunt, United States v. Anthony (1873)

United States v. Anthony, 24 F. Cas. 829 (C.C.N.D.N.Y. 1873) (No. 14,459) [Second Circuit]

Suffragist Susan B. Anthony was arrested for voting illegally in New York’s congressional election of 1872. Because New York restricted voting to men, Anthony was alleged to have violated the Enforcement Act of 1870 by voting “without having a lawful right to vote.” After hearing the arguments of counsel, Justice Hunt declined to submit the case to the jury and directed the jury to return a verdict of guilty. Anthony’s counsel then made a motion for a new trial, which Hunt denied.

Anthony claimed that she had a right to vote under the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed the privileges and immunities of United States citizenship. Hunt followed two recent Supreme Court precedents—the Slaughterhouse Cases (1873) and Bradwell v. Illinois (1873)—both of which defined the rights associated with national citizenship narrowly and held that most rights could be protected only by the states. Accordingly, he held that voting did not constitute a privilege or immunity of national citizenship. Each state made its own laws regarding the qualifications of voters, with the only restriction being the Fifteenth Amendment’s prohibition of discrimination based on race.

Hunt also rejected Anthony’s argument that she did not knowingly violate the law because she had a good faith belief that she was entitled to vote. He held that ignorance of the law did not excuse her. “She voluntarily gave a vote which was illegal,” he wrote, “and thus is subject to the penalty of the law.”

On the motion for a new trial, Hunt was called on to decide whether he had violated the Constitution by not submitting the case to the jury. “[I]n cases where the facts are all conceded, or where they are proved and uncontradicted by evidence,” he asserted, “it has always been the practice of the courts to take the case from the jury and decide it as a question of law. No counsel has ever disputed the right of the court to do so. No respectable counsel will venture to doubt the correctness of such practice, and this in cases of the character which are usually submitted to a jury.” Because he had already determined that Anthony was not a legal voter, and that her subjective intent was irrelevant, he concluded that there was nothing for the jury to decide.

Anthony was fined $100, but swore she would not pay, and the fine was never collected. The law did not provide for an appeal, and Hunt’s decision not to jail her meant that she could not apply to the Supreme Court for a writ of habeas corpus. In Minor v. Happersett (1875), the Supreme Court confirmed Hunt’s view that the Reconstruction Amendments did not grant women the right to vote. The Court held in Sparf and Hansen v. United States (1895) that a federal judge may not peremptorily instruct a jury to find the accused guilty.