You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

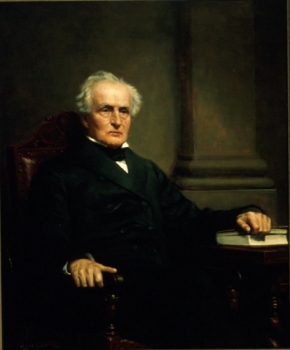

Associate Justice William Strong, Taylor v. Rockefeller (1878)

Taylor v. Rockefeller, 23 F. Cas. 792 (C.C.W.D. Pa. 1878) (No. 13,802) [Third Circuit]

Taylor was not an exceptional case, but it illustrated an important development in the jurisdiction of the federal courts. In Strawbridge v. Curtiss (1806), the Supreme Court had held that the federal courts could not exercise diversity jurisdiction over a case unless complete diversity existed, i.e., no plaintiff was a citizen of the same state as any defendant. During Reconstruction, however, Congress expanded the jurisdiction of the federal courts in the hopes of protecting African Americans and white Republicans in the South from bias in state courts. The Separable Controversy Act of 1866 provided that a portion of a suit involving diverse parties could be removed from state to federal court if that portion could be resolved on its own, without the participation of nondiverse parties.

Soon after, Congress broadened removal further in the Jurisdiction and Removal Act of 1875. The act nullified the complete diversity requirement of Strawbridge by providing that a plaintiff or defendant that was a party to a separable controversy in state court could remove the entire suit to federal court. Federal courts were thereby permitted to hear state law claims involving nondiverse parties. It was this provision of the statute that was at issue in Taylor.

The two plaintiffs, who brought their case in Pennsylvania state court, were citizens of New York and Pennsylvania. The two defendants who sought to remove the case to federal court were citizens of Ohio, although other defendants were citizens of New York and Pennsylvania. The plaintiffs asserted without explanation that the federal court lacked jurisdiction over the case and that it therefore should be remanded to the state court. Justice Strong read the 1875 act broadly, interpreting it as having been “intended to confer on the circuit courts, all the jurisdiction, which, under the constitution, it was in the power of congress to bestow.” “[I]t is certain,” he continued, “that the act of 1875 confers a right to remove cases which could not have been removed under any former act.”

Analyzing the facts of the case at hand, Strong believed it to be clear that there was a controversy wholly between the Ohio defendants and the plaintiffs that could be fully determined as to those parties. In fact, it appeared to Strong that the Ohio defendants were not only the main defendants in the suit, but the only ones that were indispensable. The dispute centered on a contract for the purchase and operation of oil lands and the sale of crude petroleum. The plaintiffs were named as trustees authorized to manage the land for the benefit of the Ohio defendants and others. The other defendants in the suit were not named in the contract, however. Their only connection with the case was that the Ohio defendants were acting as their trustees, which did not link them directly with the plaintiffs. Strong nevertheless made clear that even had the separable controversy not been the main part of the suit, the case would have been no less removable under the 1875 act. He denied the plaintiffs’ motion to remand the case to the state court.