You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

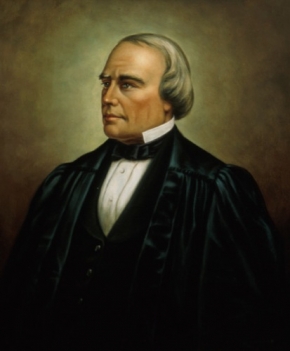

Associate Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis, Taylor v. Morton (1855)

Taylor v. Morton, 23 F. Cas. 784 (C.C.D. Mass. 1855) (No. 13,799) [First Circuit], affirmed, 67 U.S. 481 (1863)

In Taylor, Justice Curtis upheld a federal statute although it seemingly conflicted with the terms of a prior treaty between the United States and Russia. The 1832 treaty provided that Russian products would not be subjected to duties higher than those on “like” products from other nations. An 1842 tariff act, however, placed a $40 per ton tax on all raw hemp except that from India, which carried a duty of only $25 per ton. The plaintiffs, importers of Russian hemp, argued that the treaty required that they pay a rate of only $25 rather than $40.

Justice Curtis began by noting that the Constitution referred to both treaties and laws, as well as the Constitution itself, as the supreme law of the land but did not explicitly elevate one type of law over another. Judicial principles had established the Constitution as the highest law, but the Supreme Court had not determined the relative supremacy of statutes and treaties. Thus, neither source of law automatically superseded the other to provide the rule of decision in the case.

The question was not, in Curtis’s view, whether the treaty was inconsistent with the statute but whether inconsistency was a question that was appropriate for the court to decide. “If the act of congress, because it is the later law, must prescribe the rule by which this case is to be determined,” he wrote, “we do not inquire whether it proceeds upon a just interpretation of the treaty, or an accurate knowledge of the facts of likeness or unlikeness of the articles, or whether it was an accidental or purposed departure from the treaty; and if the latter, whether the reasons for that departure are such as commend themselves to the just judgment of mankind.” Those questions were solely the province of Congress, which had the power to regulate trade with foreign nations and therefore had the power to repeal or modify existing laws on the subject.

Congress, Curtis held, had the authority to legislate in a manner inconsistent with existing treaties as long as the subject was within its legislative authority. To hold that Congress could not do so, he reasoned, would rob the nation of its independence, because Congress would not be able to legislate on a particular subject without the consent of a foreign power. However, it was not the job of the federal courts to determine whether Congress had contravened a treaty. “Those powers,” he wrote, “have not been confided by the people to the judiciary, which has no suitable means to exercise them; but to the executive and the legislative departments of our government. They belong to diplomacy and legislation, and not to the administration of existing laws.”

Moreover, Curtis noted, if he were to conclude that the tariff act must be modified in accordance with the treaty, there would be no clear choice between reducing the tariff on Russian hemp to $25 or raising the tariff on Indian hemp to $40, as either would satisfy the treaty. As a result, the duties the plaintiffs had paid were assessed validly and they could not succeed on their claim. The Supreme Court held in accordance with Taylor when it decided The Cherokee Tobacco in 1870. In that case, the Internal Revenue Act of 1868, which taxed liquor and tobacco, was held to supersede a treaty with the Cherokees under which they were permitted to sell such items without taxes. The overriding of a treaty was a political question, according to the Court, and any redress lay with Congress and not the judiciary.