You are here

Circuit Court Opinions:

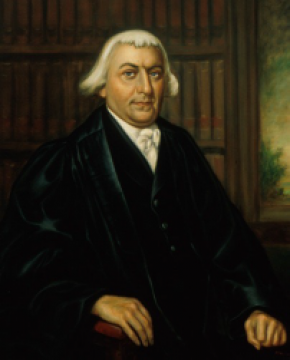

Associate Justice James Iredell, Minge v. Gilmour (1798)

Minge v. Gilmour, 17 F. Cas. 440 (C.C.D.N.C. 1798) (No. 9,631) [Southern Circuit]

Minge v. Gilmour was a complicated property dispute that hinged in part on whether a North Carolina statute of 1778, which applied retroactively, was void because of the state constitution’s ban on ex post facto laws. David Minge had possessed the land in question in fee tail, a form of ownership mandating that property pass down to the owner’s heirs. The fee tail, which created a perpetuity, was unpopular among Americans because it had contributed to the formation of a permanent landed aristocracy in England. When North Carolina enacted its first state constitution in 1776, the document expressed a public policy against perpetuities and directed the future legislature to prevent them.

The state legislature soon acted to ban perpetuities. The statute operated retroactively to convert Minge’s fee tail into a fee conditional with the result that he was free to sell the estate rather than bequeathing it to his son. Minge sold the property, and after his death, his son brought an action against the purchaser, claiming that the defendant’s title was invalid. The plaintiff rested his claim in part on the ground that the state statute banning perpetuities was an unconstitutional ex post facto law because of its retroactive application. If the act was invalid, his father’s sale of the property had violated the original terms of ownership and could not stand.

Justice Iredell construed the state constitution’s ban on ex post facto laws to apply only to criminal laws. Public policy supported this view, he asserted, because it was fundamentally unjust to punish someone for an act that was innocent at the time it was committed. Iredell pointed to the “arbitrary parliamentary punishments” existing in England in explaining why the prohibition was necessary. By contrast, he continued, it would be against public policy to ban retroactive laws transferring property from one to another. Iredell listed several instances in which the legislature might have to divest someone of a property right, such as for the building of roads, fortifications, and lighthouses.

The Minge case was a precursor to Calder v. Bull (1798), in which the Supreme Court held that the U.S. Constitution’s ban on ex post facto laws applied only to criminal, and not civil, legislation.