Historical Context

Among the many issues debated at the time of the nation’s founding was the appropriate balance of power between the national government and the states. Federalists, who supported the ratification of the Constitution, advocated a strong central government that would bind the states together as one nation. Anti-Federalists were concerned that an excessively powerful federal government would overwhelm the states and undermine their existence as independent political units.

The debate over federalism took place in several different contexts, including discussions about the plan for the federal judiciary laid out in Article III of the Constitution. The drafters of the Constitution defined the judicial power of the United States in a way that troubled the Anti-Federalists. Article III included within the judicial power suits between states, between a state and citizens of another state, and between a state and foreign states, citizens, or subjects. During debates over ratification, three states proposed placing explicit limits on suits against states, to no avail.

Those who opposed allowing states to be sued in federal court had several concerns. The states had run up significant debts in the course of fighting the Revolutionary War. Although many of these debts had been assumed by the federal government under Alexander Hamilton’s economic plan of 1790, state officials felt threatened by the possibility of being inundated with further claims by citizens of other states. They also feared being brought into federal court by frequent challenges to state land grants. A less concrete but equally important apprehension was based on the concept of state sovereignty. If states could be sued in federal court, many believed, they would cease to be sovereign and independent political units and be left entirely at the mercy of the federal government. All of these concerns came to a head when the Supreme Court decided Chisholm v. Georgia.

Legal Debates before Chisholm

Sovereign immunity is a judicial doctrine that forbids bringing suit against a government without its consent. As Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes once explained the concept, an entity which makes law must be superior to that law. The origin of the doctrine is uncertain; many have attributed it to English common law based on a statement in Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Law of England, a 1765 book upon which American lawyers relied during the founding period. Blackstone’s assertion that “no suit or action can be brought against the king, even in civil matters, because no court can have jurisdiction over him,” was an overstatement, however.

The delegates to the Constitutional Convention did not debate the issue of state sovereign immunity, but Article III defined the judicial power in language suggesting that states would be subject to suits by individuals in the federal courts. This possibility became a point of contention during the debates over ratification of the Constitution. Anti-Federalist George Mason of Virginia asked, “Is the sovereignty of the State to be arraigned like a culprit, or private offender? Will the States undergo this mortification?” Patrick Henry complained that if states could be sued for debts, holders of the “immense quantity of depreciated Continental paper money in circulation at the conclusion of the war” would be able to demand repayment of the face value of these notes “shilling for shilling.”

Federalists such as Alexander Hamilton, John Marshall, and James Madison tried to assuage such concerns by asserting that states would not be forced to stand as defendants in the federal courts, regardless of what the language of Article III might suggest. Hamilton wrote in Federalist no. 81, “It is inherent in the nature of sovereignty not to be amenable to the suit of an individual without its consent.” During ratification debates in Virginia, Madison argued that the states would have to sue in federal court in order to bring a claim against a citizen of another state, but that the states would enjoy immunity unless “a state shall condescend to be a party.” Marshall echoed Madison, asserting, “It is not rational to suppose that the sovereign power shall be dragged before a Court. The intent is, to enable States to recover claims of individuals resident in other States.” Patrick Henry scoffed at these assertions, pointing once again to the language of Article III providing for suits involving states “without discriminating between plaintiff and defendant.”

The Case

Although not decided until 1793, the Chisholm case had its origins in the early years of the Revolutionary War. In 1777, American troops stationed near Savannah, Georgia, needed supplies. Two commissioners, authorized to act on behalf of the government of Georgia, purchased the necessary items from Robert Farquhar, a merchant from South Carolina. Although the commissioners were provided with funds from the state treasury in order to pay Farquhar, they failed to do so. Farquhar died in 1784, still not having been paid. The executor of his estate, Alexander Chisholm, petitioned the state of Georgia for payment but the legislature denied the petition in 1789.

Following the denial of his petition, Chisholm brought suit against the state in the U.S. Circuit Court for the District of Georgia. The governor and attorney general of Georgia took the position that the state possessed sovereign immunity and could not be forced to appear as a defendant. The case was heard by Supreme Court Justice James Iredell, riding circuit, and U.S. District Judge Nathaniel Pendleton, both of whom agreed that the court lacked jurisdiction. In 1792, Chisholm instituted suit in the Supreme Court of the United States, where Georgia once again claimed sovereign immunity.

The Supreme Court’s Ruling

The Supreme Court ruled 4–1 that Georgia did not possess sovereign immunity and was subject to suit by individual plaintiffs in federal court. Each justice wrote a separate opinion, with Chief Justice John Jay and Justices John Blair, Jr., James Wilson, and William Cushing in the majority, and Justice James Iredell in dissent. Chief Justice Jay pointed out that Georgia could not base its objection on the mere fact that it was made a defendant in federal court, because the Constitution provided for suits between states, in which states would inevitably be defendants. The objection, therefore, was premised on the fact that the plaintiffs were individual citizens of another state. “That rule is said to be a bad one,” wrote Jay, “which does not work both ways.” In other words, if Georgia maintained the right to sue citizens of other states in federal court, it would be unjust for those citizens to lack the ability to sue Georgia.

Jay then turned to the language of the Constitution, which extended the judicial power “to controversies between a state and citizens of another state.” These words, he contended, were “express, positive, free from ambiguity, and without room” for implied exceptions. Had the drafters intended to limit this clause to suits in which a state was a plaintiff, they could have done so easily. To embrace such an exception would, Jay wrote, “contradict and do violence to the great and leading principles of a free and equal national government, one of the great objects of which is, to ensure justice to all: To the few against the many, as well as the many against the few.”

Whereas most of the justices based their decision on the text of the Constitution, James Wilson—one of the primary drafters of the Constitution—took a different approach. In his view, the case depended on the answer to the question, “do the people of the United States form a Nation?” True sovereignty, Wilson reasoned, belonged to the people, who by ratifying the Constitution had bound themselves to the nation’s laws. States, like the individuals composing them, must not be exempt from enforcement of those laws.

In his dissent, Justice Iredell asserted that every state was “completely sovereign” other than where its powers had been delegated to the federal government. According to Iredell, no suit by private citizens against a state could proceed without the state’s consent unless there was English common-law precedent to support such an action. Finding an English case allowing a claim against the Crown to proceed inapplicable to the present case, Iredell believed that the Supreme Court lacked jurisdiction over the plaintiffs’ claim against Georgia.

Aftermath and Legacy

The Chisholm ruling provoked immediate shock and outrage among government officials in Georgia and other states. The governor of Georgia, Edward Telfair, gave an address to the General Assembly in which he proclaimed that “an annihilation of [the state’s] political existence must follow,” if more suits like Chisholm’s were filed. The Georgia House of Representatives passed a resolution providing for the death penalty to be imposed on anyone attempting to enforce a judgment against the state (the state senate took no action on the resolution, however).

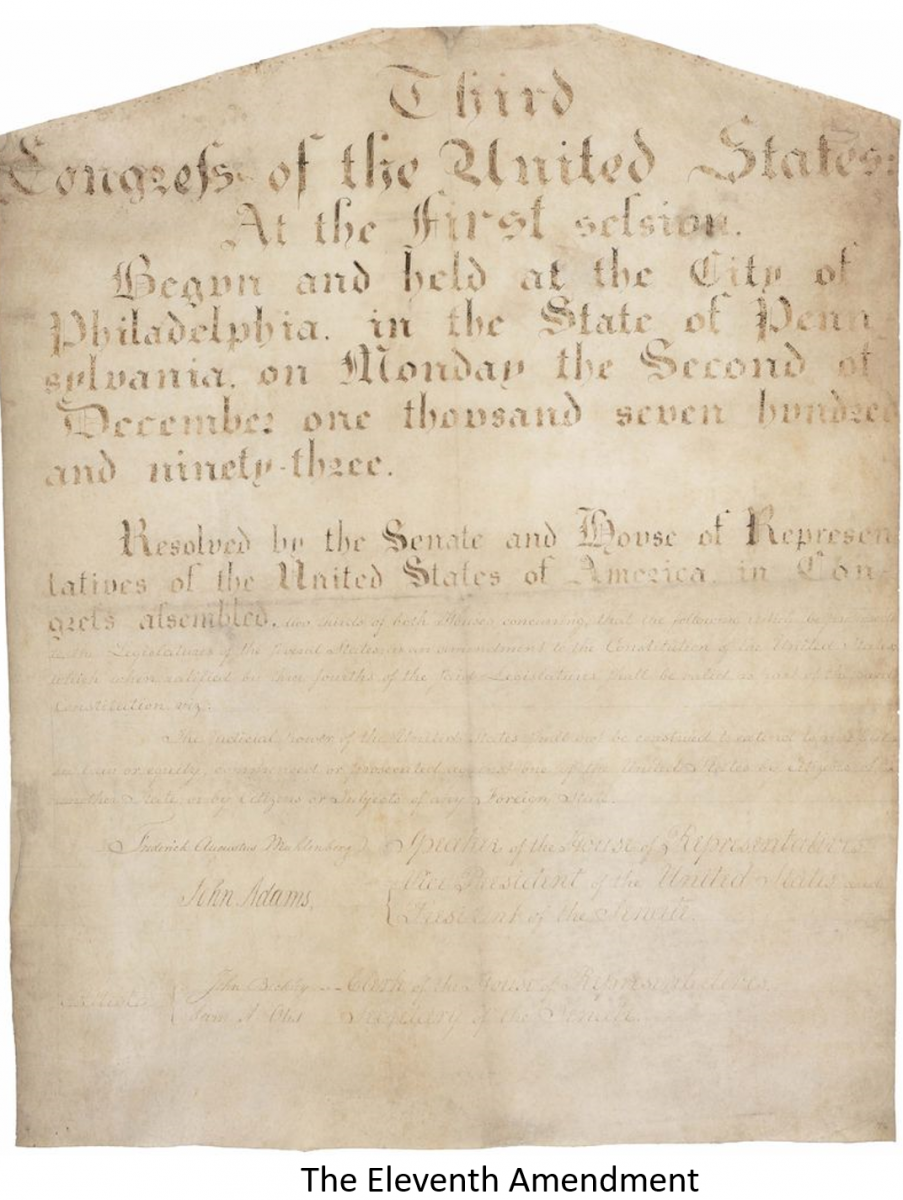

Less than a year later, Congress passed the Eleventh Amendment, which was ratified by the states on February 7, 1795, but did not go into effect until 1798. The amendment provided that “The Judicial power of the United States shall not be construed to extend to any suit in law or equity, commenced or prosecuted against one of the United States by Citizens of another State, or by Citizens or Subjects of any Foreign State.” In later decades, the Supreme Court interpreted the Eleventh Amendment broadly, holding that it precluded federal court lawsuits against states in contexts other than those specified, including suits against a state by its own citizens.

The Supreme Court had issued a judgment in favor of Chisholm in 1794, but the judgment was never enforced. After ordering an inquiry to determine the amount of damages Georgia should pay, the Court granted several continuances of the case. In 1798, after the Eleventh Amendment took effect, the Court removed all suits against states by individual plaintiffs, including Chisholm, from its docket.

Discussion Questions

- What is the reasoning behind sovereign immunity? Do you find it persuasive?

- Under what circumstances, if any, should individuals be able to sue a state government?

- What do the Chisholm case and its immediate aftermath tell us about the relationship between Congress and the Supreme Court in the early republic?

- Would the Chisholm decision have been correct if the justices had believed the plain language of Article III to provide for suits against states, but also believed that the drafters of the Constitution had not intended to allow such suits?