You are here

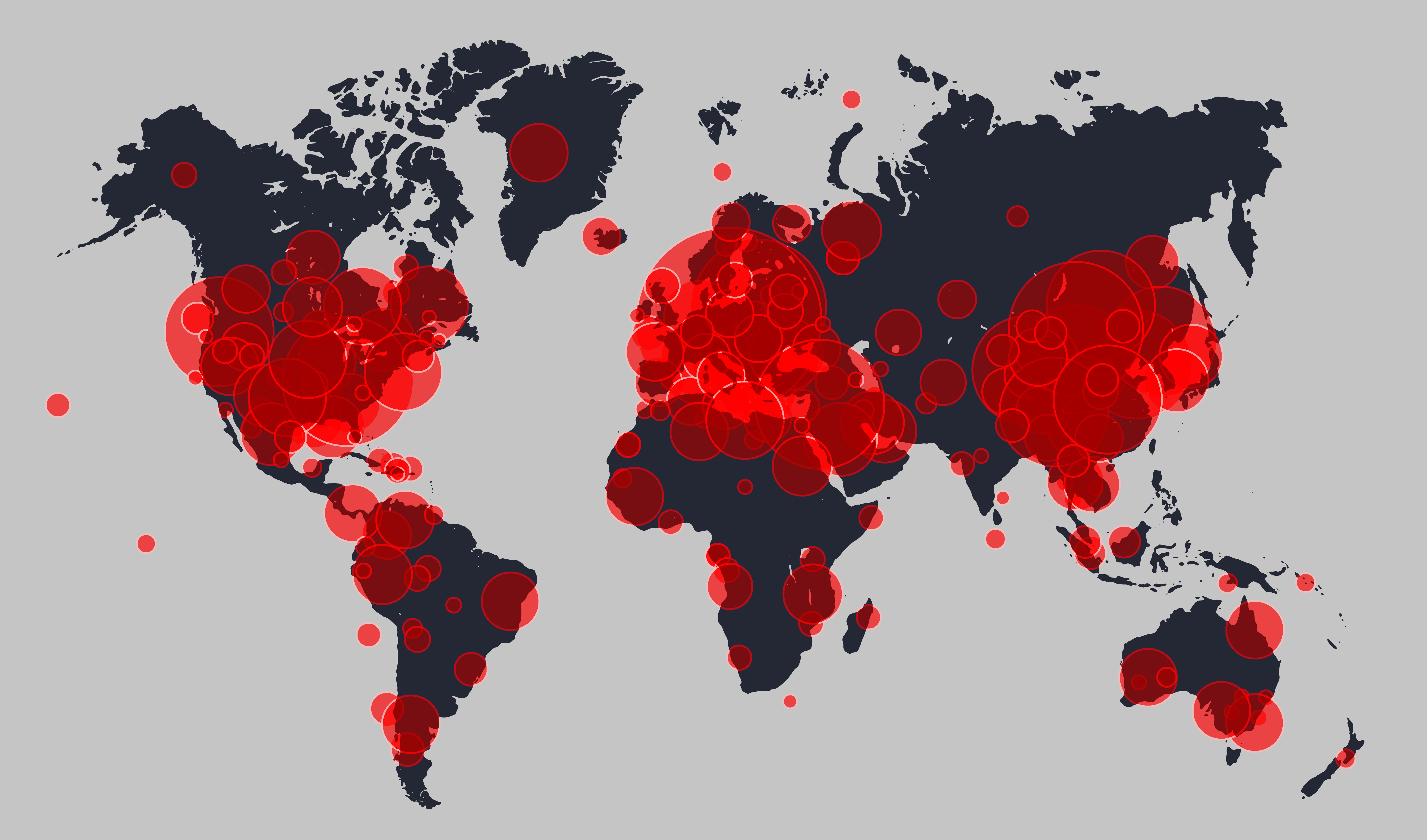

Judiciaries Around the World Rally and Innovate to Meet the Challenge of COVID-19

UPDATE: May 26, 2020

The global judicial community has developed resources for judges and administrative staff that address court operations, resilience, and access to justice during the COVID-19 crisis. A selection can be found here.

April 28, 2020

In early April, the International Judicial Relations Office reached out to colleagues around the world, asking them to share their judiciary’s experience with preserving access to justice during the coronavirus crisis. Many responded with compelling descriptions of efforts to provide essential court services while protecting the safety of judges, court personnel, litigants and the public.

Their strategies vary, depending upon the availability of court technology and the pervasiveness of the pandemic in their communities. Most national governments have imposed strict physical distancing measures, often for periods that have been extended into May. Courts in Egypt and Jordan are hearing only critical, mostly criminal, matters. In many countries, including Argentina, Nigeria, the Philippines and Uzbekistan, the Supreme Court has limited in-person proceedings to urgent matters. The Supreme Court of Japan issued a national decree suspending most court business and advising the public to check with their local courts to confirm which types of cases are being heard.

Court technology in Japan is not widespread. Many courts do not have e-filing, constraining the ability of some judges to work on their cases from home. Federal courts in Australia are conducting hearings in civil matters by video link. Judges login from their chambers, with limited staff, and the attorneys often appear from their offices. Brazil’s Federal Supreme Court receives pre-recorded oral arguments before its scheduled sittings; lawyers may send video or audio, in compliance with designated quality standards. The Court’s weekly sessions are conducted virtually, as are proceedings in the country’s lower federal courts. In contrast, most hearings in Brazil’s less technologically equipped regional courts have been postponed. Courts in China had already introduced online dispute resolution in many regions, for civil matters; this practice has expanded considerably during the period of court closures. In Papua New Guinea, although the courts are closed, urgent applications are being filed using the judiciary’s online case management system. In Argentina, provincial courts with more sophisticated technology have implemented electronic case filing and are able to operate remotely. Access to technology also varies by region in India. Provincial courts with capacity hold hearings by video.

Bulgarian judges take turns going to courthouses to preside over urgent criminal matters. When not on call, they work on their cases from home, with some emergency hearings handled via videoconference. The judiciary’s summer break (usually from mid-July until September) has been cancelled. In Georgia, almost all court proceedings are being conducted remotely. However, as is likely the case in many countries, there is no public access to e-proceedings. Georgian civil society groups are protesting this lack of transparency. Hungary’s National Assembly declared a “state of danger,” empowering the government to take extraordinary measures to preserve the health and economic stability of the country. The Constitutional Court has been authorized to continue operations using technology and hearings by video. This capacity has been applauded by civil society, as the court was created, in part, to be a check on the executive branch.

Nigeria does not have a developed court technology infrastructure. Lagos State is the only region able to conduct a limited number of virtual court proceedings. The judiciaries of Bangladesh and Nepal also do not have access to court technology. The courts are closed except for emergency matters such as bail hearings. In Bangladesh, a small number of judges preside over these cases, and the Supreme Court has ordered corrections officials not to produce prisoners. Nepali judges appear in court for urgent matters, on a rotating basis. In the Philippines, new Supreme Court guidelines authorize e-filing and remote proceedings. However, the availability of court technology is limited. In most cases, Filipino judges are asked to volunteer to preside over emergency proceedings. In Turkey, the courts have been closed, with special proceedings held by videoconference or, if technology is not available, in-person with physical distancing.

Another challenge mentioned by many judges is the spread of Covid-19 in the prisons. In recognition of efforts to contain the virus, some of Pakistan’s regional high courts ordered the release of prisoners incarcerated for petty crimes. These decrees were suspended by the Supreme Court. Brazil’s National Council of Justice issued a recommendation that some prisoners from at risk populations be permitted to serve their sentences from home. Argentina’s highest criminal court recommended that prisoners incarcerated on minor offenses be released. Similarly, India’s Supreme Court authorized states to release on bail prisoners accused of nonviolent offenses. A similar policy is being considered in the Philippines.

In the United States, most federal and state courts are open for only critical proceedings, with physical distancing and protective wear. Some hearings and case conferences are taking place via video or teleconference. Judges work on cases remotely, communicating regularly with their staff. The federal judiciary recently authorized judges to conduct certain criminal proceedings via video, on a temporary basis and with the consent of the defendant (https://www.uscourts.gov/news/2020/03/12/judiciary-preparedness-coronavi...). The Supreme Court cancelled its March and April argument sessions but will hold hearings in May via telephone. Justices will ask the attorneys questions in order of seniority.

The prison system in the United States is under strain, as detention facilities confront growing numbers of COVID-19 cases. The Attorney General authorized the federal Bureau of Prisons to release a limited number of vulnerable inmates to home confinement from prisons hardest hit by the coronavirus. State court operations and prisoner release policies vary considerably across the country (https://www.themarshallproject.org/2020/03/17/tracking-prisons-response-...). While some court systems have made efforts to ensure public access to virtual court proceedings, others have been criticized for failing to do so.

Although much of this shared information is anecdotal, it offers valuable insights into how national court systems throughout the world are working to preserve the rule of law while confronting an unexpected, unique, and daunting challenge.