Composition of the Courts

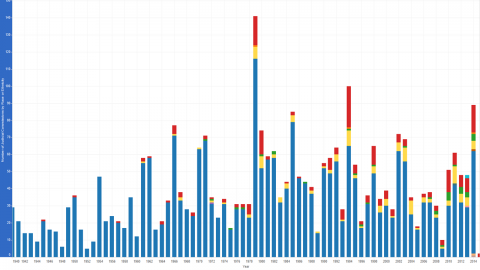

The number of Article III judges has generally risen over time, reflecting the changing workload of the judiciary and the geographical and population growth of the nation. Indeed, approximately one third of all Article III judges ever appointed remain on the federal bench. Congress initially authorized the appointment of 19 such judges. From 1789 through 1891, there were never more than 100 Article III judges serving at any given point in time. During the twentieth century, however, the judiciary began to grow more rapidly. From 1940 to 1970, for example, the number of positions authorized by Congress more than doubled (from 257 to 521).[1]

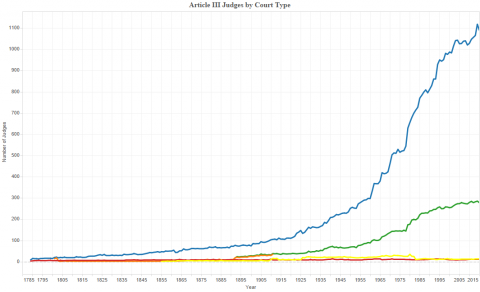

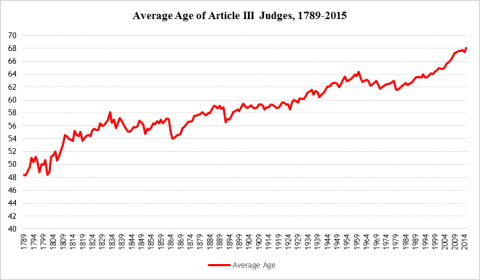

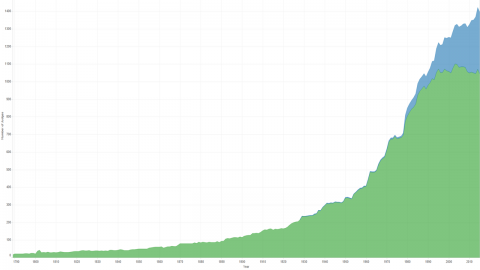

The number of authorized judgeships has not always reflected the actual number of judges working in Article III courts. Indeed, due to deaths and other departures, as well as the variable length of the judicial confirmation process, the full allocation of Article III judgeships has seldom been filled. In 1919, moreover, Congress created senior judge status. This allowed “any judge other than a justice of the Supreme Court” to hear a reduced number of cases once he or she reached certain age and length-of-service milestones. Congress extended a similar option to Supreme Court justices in 1937, although justices following this path are generally referred to as “retired,” rather than “senior,” justices and do not continue to decide cases at the Supreme Court level.[2] When a judge or justice takes senior status, his or her place may be filled by a newly appointed and confirmed judge or justice while his or her predecessor continues to perform judicial work (see Age and Experience of Judges for more information about senior judges). The chart below reflects the total number of Article III judges serving on an annual basis.[3] You can view a specific date range in closer detail using the slide control to the right of the chart.

These data do not fully express changes in the workload of the federal judiciary or in the allocation of that work among various courts. Article III, section 1 of the Constitution states that “[t]he judicial power of the United States, shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish[,]” and Article I, section 8 empowers Congress “[t]o constitute Tribunals inferior to the supreme Court[.]” Since the creation of the federal judiciary in 1789, Congress has established multiple “inferior” courts. The nature and scope of these courts’ roles have changed several times over the centuries.

Initially, for instance, Congress created district and circuit courts to deal with the bulk of federal cases. District courts were the trial venues for admiralty and minor civil and criminal matters. Circuit courts had a blend of trial and appellate jurisdiction, hearing appeals on some matters from the district courts as well as major criminal and civil trials. The circuit courts were originally staffed by a combination of district court judges and Supreme Court justices, who “rode circuit” to hear cases in these courts.

Congress transformed this structure several times over the course of the nineteenth century before settling on the current system of district courts as the primary trial courts, courts of appeal (sometimes confusingly labeled “circuit courts”) hearing most appeals from the district courts, and the Supreme Court as the tribunal of final resort. Congress also frequently modified the jurisdiction of existing courts over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These changes have transformed the work and workload of the federal courts. For more detailed information on the changing scope of federal jurisdiction, see the Jurisdiction of the Federal Courts timeline on this site.

Congress also created additional courts with jurisdiction over particular types of suits. The longest-lasting of these was the Court of Claims, created in 1855, which heard claims for monetary compensation against the federal government. Later, Congress created specialized courts to hear cases involving disputes over customs, patents, and international trade.

This evolving system is reflected in the chart below, which shows the timespans of each of the different Article III court types. The entry for the U.S. Court of Customs and Patent Appeals includes that court's predecessor, the U.S. Court of Customs Appeals. For more information about the role of each of the Article III courts, see the Courts, Caseloads, and Jurisdictions page on this site.

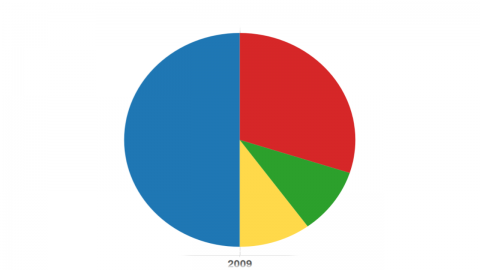

The two interactive graphs below reflect trends in the distribution of the nation’s judges between these courts. The first shows the distribution of authorized judgeships by court type.[4]

Due to the appointment of existing judges to new judicial offices, trends in longevity, and the prevalence of judges assuming senior status, the overall composition of the bench has frequently differed from number of authorized judgeships for each court type (for information on these trends, see Age and Experience). The graph below shows the composition of the sitting members of the bench over time by court type. You can select a particular court type or time period using the controls to the right of the graph.[5]

[1] In 2008, Congress reallocated one judicial position, moving a judgeship from the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. This move was authorized on January 7, 2008, but did not take effect until January 21, 2009, with the result that the charts on this page reflect a total number of authorized judgeships in 2008 of 859. See Pub. L. No. 110-177. Researchers interested in more information about this data should consult the website of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. These charts do not distinguish between temporary and permanent judgeships. Thus, legislation making several temporary judgeships permanent in 2024 is not reflected on this page.

[2] 40 Stat. 1157 (1919).

[3] The chart counts any judge who served during any part of a year. Judicial service is counted as beginning on the date of commission and ending on the date of termination. The service of judges given recess appointments who were not subsequently confirmed by the Senate is counted from the date of the recess appointment to the date the appointment terminated. Where a judge left the judiciary and was replaced within a single year, both judges are counted. Researchers seeking exact dates of judicial service should consult the Biographical Directory Export or the FJC’s Judicial Succession Charts, which are available for each court through the Courts page.

[4] Chart based on data from the Administrative Office of the United States Courts. The Supreme Court of the District of Columbia, which was eventually renamed the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, is included in the U.S. district court totals. For the purposes of this chart, all former circuit courts are counted as belonging to the same court type. Additionally, this chart lists judges of the circuit courts for the District of Columbia and the California Circuit, which are not included in Administrative Office tabulations. With the exceptions of those courts, from 1789 to 1800 and from 1802 to 1869 regional circuit courts were staffed by a combination of district judges and Supreme Court justices and thus did not have any authorized judgeships. From 1891 to 1911, several judges held simultaneous commissions for both U.S. circuit courts and U.S. courts of appeals. These judgeships are included in the totals for both court types.

[5] The chart counts any judge who served during any part of a year. No distinction is made between active and senior judges, including Supreme Court justices who were retired from active service. Judicial service is counted as beginning on the date of commission and ending on the date of termination. The service of judges given recess appointments who were not subsequently confirmed by the Senate is counted from the date of the recess appointment to the date the appointment terminated. Where a judge left the judiciary and was replaced within a single year, both judges are counted.